To Shabbir Bhatti, his childhood memories from 1944 are as vivid as the colours of the Holi celebrations in his neighbourhood in Kapurthala. He remembers how the excited neighbourhood children, Hindu, Muslim and Sikh, all caked in bright colours would celebrate the festival just as they all enjoyed Eid mithai together at the end of the holy month of Ramadan.

While Shabbir was born in Lahore, in keeping with the family tradition, his parents sent him to be educated in the nearby royal city of Kapurthala when he turned five. He would live with his uncle, a wealthy landowner, while he attended primary school in the city. His new hometown, with its beautiful French and Indo-Saracenic architecture, had quite an impact on young Shabbir. Kapurthala was the capital of erstwhile princely Kapurthala State and the seat of power of the Sikh Ahluwalia Dynasty. “It was a beautiful city full of gardens and royal palaces,” he remembers. “And one of my cousins worked as the private assistant to the tikka (ruler) of the state so he used to take me in to work with him all the time and so I had almost unfettered access to these beautiful palaces.”

India and Pakistan were still three years away from their painful birth as independent nation states. In five-year-old Shabbir’s neighbourhood in Kapurthala, there was no indication of the turmoil to come. “Most of our neighbours were Hindu and Sikh and I never remember any feeling animosity between anyone. In fact, one of my closest friends was Sikh and I distinctly remember how close we were and how we used to go to the beautiful royal palace grounds together to play badminton,” says Shabbir. He remembers his ‘mohalla’ (neighbourhood) like it was yesterday. “Our mohalla, Loha Mandi, was a very well planned part of town. Proper drainage and paved streets. And my uncle’s beautiful house. He was a wealthy man. And my school was so close to his house that I could walk there and back. I could hear the school clock tower ringing from home.”

Shabbir’s memories of the harmony of his mohalla are in stark contrast to the horrors that the communal tensions preceding and following the partition of the country would bring. Maybe it was a child’s innocence to what was happening around him but to Shabbir the horrors of partition came swiftly and without any warning. “All of a sudden one day I remember I had to leave with my mother and go to one of the villages where my uncle owned land. The city, my home until yesterday, had apparently become too dangerous for us,” says Shabbir. “I did not really understand why or what was happening but the family elders told me we were going to this new country called Pakistan.” That was November, 1947.

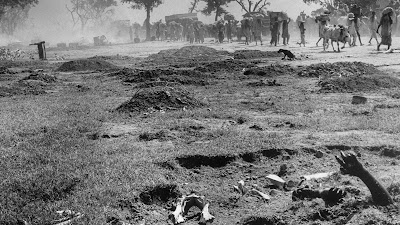

Independence had finally come after a long, protracted struggle. But for Shabbir and his family it wasn’t a time for celebration. All of a sudden they found themselves on the wrong side of this new international border. Punjab had been split and Lahore, Shabbir’s family home, was now in Pakistan. Fearing religious persecution, millions of people were routinely crossing this new border. In Lahore, Shabbir’s father was waiting anxiously for his family to make the crossing. Shabbir and his mother left with a huge group of people and started walking towards the new border crossing at Wagah. From their life in India they only took what they could carry on their backs. “It was a huge sea of people walking towards Wagah. Conditions were dire, we didn’t have any food or drinking water and people had resorted to drinking from dirty ponds just to keep themselves going. Death was everywhere and people had almost hardened to it. Scores of people died en route and their family members would just bury them in makeshift graves and keep moving on,” he says. “This horror was the opposite of my life in my mohalla in Kapurthala. I had experienced the best and now the absolute worst within those three years of my life and nothing in between.”

1947 - A convoy of Muslims passes the remains of an earlier caravan

#1947Partition

Pic clicked by - Margaret Bourke-White

No comments:

Post a Comment